| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

| |||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Theaters of the Russian Civil War | |

|---|---|

|

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the overthrowing of the liberal-democratic Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. It resulted in the formation of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and later the Soviet Union in most of its territory. Its finale marked the end of the Russian Revolution, which was one of the key events of the 20th century.

The Russian monarchy ended with the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II during the February Revolution, and Russia was in a state of political flux. A tense summer culminated in the October Revolution, where the Bolsheviks overthrew the provisional government of the new Russian Republic. Bolshevik seizure of power was not universally accepted, and the country descended into civil war. The two largest combatants were the Red Army, fighting for the establishment of a Bolshevik-led socialist state headed by Vladimir Lenin, and the loosely allied forces known as the White Army, which functioned as a political big tent for right- and left-wing opposition to Bolshevik rule. In addition, rival militant socialists, notably the Ukrainian anarchists of the Makhnovshchina and Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, were involved in conflict against the Bolsheviks. They, as well as non-ideological green armies, opposed the Bolsheviks, the Whites and the foreign interventionists. Thirteen foreign nations intervened against the Red Army, notably the Allied intervention, whose primary goal was re-establishing the Eastern Front of World War I. Three foreign nations of the Central Powers also intervened, rivaling the Allied intervention with the main goal of retaining the territory they had received in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Soviet Russia.

The Bolsheviks initially consolidated control over most of the former empire. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was an emergency peace with the German Empire, who had captured vast swathes of the Russian territory during the chaos of the revolution. In May 1918, the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia revolted in Siberia. In reaction, the Allies began their North Russian and Siberian interventions. That, combined with the creation of the Provisional All-Russian Government, saw the reduction of Bolshevik-controlled territory to most of European Russia and parts of Central Asia. In 1919, the White Army launched several offensives from the east in March, the south in July, and west in October. The advances were later checked by the Eastern Front counteroffensive, the Southern Front counteroffensive, and the defeat of the Northwestern Army.

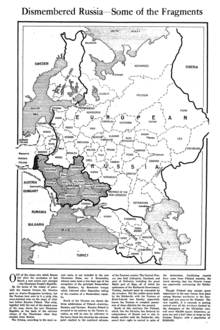

By 1919, the White armies were in retreat and by the start of 1920 were defeated on all three fronts. Although the Bolsheviks were victorious, the territorial extent of the Russian state had been reduced, for many non-Russian ethnic groups had used the disarray to push for national independence. In March 1921, during a related war against Poland, the Peace of Riga was signed, splitting disputed territories in Belarus and Ukraine between the Republic of Poland and Soviet Russia. Soviet Russia sought to re-conquer all newly independent nations of the former empire, although their success was limited. Estonia, Finland, Latvia, and Lithuania all repelled Soviet invasions, while Ukraine, Belarus (as a result of the Polish–Soviet War), Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia were occupied by the Red Army. By 1921, Soviet Russia had defeated the Ukrainian national movements and occupied the Caucasus, although anti-Bolshevik uprisings in Central Asia lasted until the late 1920s.

The armies under Kolchak were eventually forced on a mass retreat eastward. Bolshevik forces advanced east, despite encountering resistance in Chita, Yakut and Mongolia. Soon the Red Army split the Don and Volunteer armies, forcing evacuations in Novorossiysk in March and Crimea in November 1920. After that, fighting was sporadic until the war ended with the capture of Vladivostok in October 1922, but anti-Bolshevik resistance continued with the Muslim Basmachi movement in Central Asia and Khabarovsk Krai until 1934. There were an estimated 7 to 12 million casualties during the war, mostly civilians.

The Russian Empire fought in World War I from 1914 alongside France and the United Kingdom (Triple Entente) against Germany, Austria-Hungary and Ottoman Empire (Central Powers).

The February Revolution of 1917 resulted in the abdication of Emperor Nicholas II of Russia. As a result, the social-democratic Russian Provisional Government was established, and soviets, elected councils of workers, soldiers, and peasants, were organized throughout the country, leading to a situation of dual power. The Russian Republic was proclaimed in September of the same year.

The Provisional Government, led by Socialist Revolutionary Party politician Alexander Kerensky, was unable to solve the most pressing issues of the country, most importantly to end the war with the Central Powers. A failed military coup by General Lavr Kornilov in September 1917 led to a surge in support for the Bolsheviks, who took control of the soviets, which until then had been controlled by the Socialist Revolutionaries. Promising an end to the war and "all power to the Soviets", the Bolsheviks then ended dual power by overthrowing the Provisional Government in late October, on the eve of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, in what would be the second Revolution of 1917. The initial stage of the October Revolution which involved the assault on Petrograd occurred largely without any human casualties. Despite the Bolsheviks' seizure of power, they lost to the Socialist Revolutionary Party in the 1917 Russian Constituent Assembly election, and the Constituent Assembly was dissolved by the Bolsheviks in retaliation. The Bolsheviks soon lost the support of other far-left allies, such as the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, after their acceptance of the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk presented by the German Empire. Conversely, a number of prominent members of the Left Socialist Revolutionaries had assumed positions in Lenin's government and led commissariats in several areas. This included agriculture (Kolegaev), property (Karelin), justice (Steinberg), post offices and telegraphs (Proshian) and local government (Trutovsky). The Bolsheviks also reserved a number of vacant seats in the Soviets and Central Executive for the Menshevik and Left Socialist Revolutionaries parties in proportion to their vote share at the Congress. The dissolution of the Constituent Assembly was also approved by the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and anarchists, both groups were in favour of a more radical democracy.

From mid-1917 onwards, the Russian Army, the successor-organisation of the old Imperial Russian Army, started to disintegrate; the Bolsheviks used the volunteer-based Red Guards as their main military force, augmented by an armed military component of the Cheka (the Bolshevik state secret police). In January 1918, after significant Bolshevik reverses in combat, the future Russian People's Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs Leon Trotsky headed the reorganization of the Red Guards into a Workers' and Peasants' Red Army in order to create a more effective fighting force. The Bolsheviks appointed political commissars to each unit of the Red Army to maintain morale and to ensure loyalty.

In June 1918, when it had become apparent that a revolutionary army composed solely of workers would not suffice, Trotsky instituted mandatory conscription of the rural peasantry into the Red Army. The Bolsheviks overcame opposition of rural Russians to Red Army conscription units by taking hostages and shooting them when necessary in order to force compliance. The forced conscription drive had mixed results, successfully creating a larger army than the Whites, but with members indifferent towards communist ideology.

The Red Army also utilized former Tsarist officers as "military specialists" (voenspetsy); sometimes their families were taken hostage in order to ensure their loyalty. At the start of the civil war, former Tsarist officers formed three-quarters of the Red Army officer-corps. By its end, 83% of all Red Army divisional and corps commanders were ex-Tsarist soldiers.

The White movement (Russian: pre–1918 Бѣлое движеніе / post–1918 Белое движение, romanized: Beloye dvizheniye, IPA: [ˈbʲɛləɪ dvʲɪˈʐenʲɪɪ]) also known as the Whites (Белые, Beliye), was a loose confederation of anti-communist forces that fought the communist Bolsheviks, also known as the Reds, in the Russian Civil War and that to a lesser extent continued operating as militarized associations of rebels both outside and within Russian borders in Siberia until roughly World War II (1939–1945). The movement's military arm was the White Army (Бѣлая армія / Белая армия, Belaya armiya), also known as the White Guard (Бѣлая гвардія / Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya) or White Guardsmen (Бѣлогвардейцы / Белогвардейцы, Belogvardeytsi).

When the White Army was created, the structure of the Russian Army of the Provisional Government period was used, while almost every individual formation had its own characteristics. The military art of the White Army was based on the experience of World War I, which, however, left a strong imprint on the specifics of the Civil War.

During the Russian Civil War, the White movement functioned as a big tent political movement representing an array of political opinions in Russia united in their opposition to the Bolsheviks—from the republican-minded liberals and Kerenskyite social-democrats on the left through monarchists and supporters of a united multinational Russia to the ultra-nationalist Black Hundreds on the right.

The Russian Constituent Assembly had been a demand of the Bolsheviks against the Provisional Government, which kept delaying it. After the October Revolution the elections were run by the body appointed by the previous Provisional Government. It was based on universal suffrage but used party lists from before the Left-Right SR split. The anti-Bolshevik Right SRs won the elections with the majority of the seats, after which Lenin's Theses on the Constituent Assembly argued in Pravda that formal democracy was impossible because of class conflicts, conflicts with Ukraine and the Kadet-Kaledin uprising. He argued the Constituent Assembly must unconditionally accept sovereignty of the soviet government or it would be dealt with "by revolutionary means".

On December 30, 1917, the SR Nikolai Avksentiev and some followers were arrested for organizing a conspiracy. This was the first time Bolsheviks used this kind of repression against a socialist party. Izvestia said the arrest was not related to his membership in the Constituent Assembly.

On January 4, 1918, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee made a resolution saying the slogan "all power to the constituent assembly" was counterrevolutionary and equivalent to "down with the soviets".

The Constituent Assembly met on January 18, 1918. The Right SR Chernov was elected president defeating the Bolshevik supported candidate, the Left SR Maria Spiridonova (she would later break with the Bolsheviks and after the decades of gulag, she was shot on Stalin's orders in 1941). The Bolsheviks subsequently disbanded the Constituent Assembly and proceeded to rule the country as a one-party state with all opposition parties outlawed. A simultaneous demonstration in favor of the Constituent Assembly was dispersed with force, but there was little protest afterwards.

The first large Cheka repression involving the killing of libertarian socialists in Petrograd began in April 1918. On May 1, 1918, a pitched battle took place in Moscow between the anarchists and the Bolshevik police.

The Union of Regeneration was founded in Moscow in April 1918 as an underground agency organizing democratic resistance to the Bolshevik dictatorship, composed of the Popular Socialists, Right Socialist Revolutionaries, and Defensists, among others. They were tasked with propping up anti-Bolshevik forces and to create a Russian state system based on civil liberties, patriotism, and state-consciousness with the goal to liberate the country from the "Germano-Bolshevik" yoke.

On May 7, 1918, the Eighth Party Council of the Socialist Revolutionary Party commenced in Moscow and recognized the Union's leading role, putting aside political ideology and class for the purpose of Russia's salvation. They decided to start an uprising against the Bolsheviks with the goal of reconvening the Russian Constituent Assembly. While preparations were under way, the Czechoslovak Legions overthrew Bolshevik rule in Siberia, the Urals and the Volga region in late May-early June 1918 and the center of SR activity shifted there. On June 8, 1918, five Constituent Assembly members formed the All-Russian Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly (Komuch) in Samara and declared it the new supreme authority in the country. The Social Revolutionary Provisional Government of Autonomous Siberia came to power on 29 June 1918, after the uprising in Vladivostok.

At the Fifth All–Russian Congress of Soviets of July 4, 1918, the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries had 352 delegates compared to 745 Bolsheviks out of 1132 total. The Left SRs raised disagreements on the suppression of rival parties, the death penalty, and mainly, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The Bolsheviks excluded the Right SRs and Mensheviks from the government on 14 June for associating with counterrevolutionaries and seeking to "organize armed attacks against the workers and peasants" (though Mensheviks had not supported them), while the Left SRs advocated forming a government of all socialist parties. The Left SRs agreed with extrajudicial execution of political opponents to stop the counterrevolution, but opposed having the government legally pronouncing death sentences, an unusual position that is best understood within the context of the group's terrorist past. The Left SRs strongly opposed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and opposed Trotsky's insistence that no one try to attack German troops in Ukraine.

According to historian Marcel Liebman, Lenin's wartime measures such as banning opposition parties was prompted by the fact that several political parties either took up arms against the new Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, or participated in sabotage, collaboration with the deposed Tsarists, or made assassination attempts against Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders. Liebman noted that opposition parties such as the Cadets and Mensheviks who were democratically elected to the Soviets in some areas, then proceeded to use their mandate to welcome in Tsarist and foreign capitalist military forces. In one incident in Baku, the British military, once invited in, proceeded to execute members of the Bolshevik Party who had peacefully stood down from the Soviet when they failed to win the elections. As a result, the Bolsheviks banned each opposition party when it turned against the Soviet government. In some cases, bans were lifted. This banning of parties did not have the same repressive character as later bans enforced under the Stalinist regime.

In December 1917, Felix Dzerzhinsky was appointed to the duty of rooting out counter-revolutionary threats to the Soviet government. He was the director of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission (aka Cheka), a predecessor of the KGB that served as the secret police for the Soviets.

The Bolsheviks had begun to see the anarchists as a legitimate threat and associate criminality such as robberies, expropriations and murders with anarchist associations. Subsequently, the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) decided to liquidate criminal recklessness associated with anarchists and disarm all anarchist groups in the face of their militancy.

From early 1918, the Bolsheviks started physical elimination of opposition, other socialist and revolutionary fractions. Anarchists were among the first:

Of all the revolutionary elements in Russia it is the Anarchists who now suffer the most ruthless and systematic persecution. Their suppression by the Bolsheviki began already in 1918, when — in the month of April of that year — the Communist Government attacked, without provocation or warning, the Anarchist Club of Moscow and by the use of machine guns and artillery "liquidated" the whole organisation. It was the beginning of Anarchist hounding, but it was sporadic in character, breaking out now and then, quite planless, and frequently self-contradictory.

On 11 August 1918, prior to the events that would officially catalyze the Red Terror, Vladimir Lenin had sent telegrams "to introduce mass terror" in Nizhny Novgorod in response to a suspected civilian uprising there, and to "crush" landowners in Penza who resisted, sometimes violently, the requisitioning of their grain by military detachments:

Comrades! The kulak uprising in your five districts must be crushed without pity ... You must make example of these people.

- (1) Hang (I mean hang publicly, so that people see it) at least 100 kulaks, rich bastards, and known bloodsuckers.

- (2) Publish their names.

- (3) Seize all their grain.

- (4) Single out the hostages per my instructions in yesterday's telegram.

Do all this so that for miles (versts) around people see it all, understand it, tremble, and tell themselves that we are killing the bloodthirsty kulaks and that we will continue to do so ...

Yours, Lenin.

P.S. Find tougher people.

In a mid-August 1920 letter, having received information that in Estonia and Latvia, with which Soviet Russia had concluded peace treaties, volunteers were being enrolled in anti-Bolshevik detachments, Lenin wrote to E. M. Sklyansky, deputy chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic:

Great plan! Finish it with Dzerzhinsky. While pretending to be the "greens" (we will blame them later), we will advance by 10–20 miles (versts) and hang kulaks, priests, landowners. Prize: 100.000 rubles for each hanged man.

Leonid Kannegisser, a young military cadet of the Imperial Russian Army, assassinated Moisey Uritsky on August 17, 1918, outside the Petrograd Cheka headquarters in retaliation for the execution of his friend and other officers.

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: incomplete sentence starting with 'and sought to eliminate...'. Next sentence explains 'the term', which hasn't been introduced. Please help improve this section if you can. (August 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

On August 30, the SR Fanny Kaplan unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate Lenin, who sought to eliminate political dissent, opposition, and any other threat to Bolshevik power. As a result of the failed attempt on Lenin's life, he began to crack down on his political enemies in an event known as the Red Terror. More broadly, the term is usually applied to Bolshevik political repression throughout the Civil War (1917–1922),

During interrogation by the Cheka, she made the following statement:

My name is Fanya Kaplan. Today I shot Lenin. I did it on my own. I will not say from whom I obtained my revolver. I will give no details. I had resolved to kill Lenin long ago. I consider him a traitor to the Revolution. I was exiled to Akatui for participating in an assassination attempt against a Tsarist official in Kiev. I spent 11 years at hard labour. After the Revolution, I was freed. I favoured the Constituent Assembly and am still for it.

Kaplan referenced the Bolsheviks' growing authoritarianism, citing their forcible shutdown of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918, the elections to which they had lost. When it became clear that Kaplan would not implicate any accomplices, she was executed in Alexander Garden. The order was carried out by the commander of the Kremlin, the former Baltic sailor P. D. Malkov and a group of Latvian Bolsheviks on September 3, 1918, with a bullet to the back of the head. Her corpse was bundled into a barrel and set alight. The order came from Yakov Sverdlov, who only six weeks earlier had ordered the murder of the Tsar and his family.

These events persuaded the government to heed Dzerzhinsky's lobbying for greater terror against opposition. The campaign of mass repressions would officially begin thereafter. The Red Terror is considered to have officially begun between 17 and 30 August 1918.

Protests against grain requisitioning of the peasantry were a major component of the Tambov Rebellion and similar uprisings; Lenin's New Economic Policy was introduced as a concession.

The policies of "food dictatorship" proclaimed by the Bolsheviks in May 1918 sparked violent resistance in numerous districts of European Russia: revolts and clashes between the peasants and the Red Army were reported in Voronezh, Tambov, Penza, Saratov and in the districts of Kostroma, Moscow, Novgorod, Petrograd, Pskov and Smolensk. The revolts were bloodily crushed by the Bolsheviks: in the Voronezh Oblast, the Red Guards killed sixteen peasants during the pacification of the village, while another village was shelled with artillery in order to force the peasants to surrender and in the Novgorod Oblast the rebelling peasants were dispersed with machine-gun fire from a train sent by a detachment of Latvian Red Army soldiers. While the Bolsheviks immediately denounced the rebellion as orchestrated by the SRs, there is actually no evidence that they were involved into peasant violence, which they deemed as counterproductive.

The Western Allies armed and supported opponents of the Bolsheviks. They were worried about a possible Russo-German alliance, the prospect of the Bolsheviks making good on their threats to default on Imperial Russia's massive foreign debts and the possibility that Communist revolutionary ideas would spread (a concern shared by many Central Powers). Hence, many of the countries expressed their support for the Whites, including the provision of troops and supplies. Winston Churchill declared that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle". The British and French had supported Russia during World War I on a massive scale with war materials.

After the treaty, it looked like much of that material would fall into the hands of the Germans. To meet that danger, the Allies intervened with Great Britain and France sending troops into Russian ports. There were violent clashes with the Bolsheviks. Britain intervened in support of the White forces to defeat the Bolsheviks and prevent the spread of communism across Europe.

The German Empire created several short-lived buffer states within its sphere of influence after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk: the United Baltic Duchy, Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, Kingdom of Lithuania, Kingdom of Poland, the Belarusian People's Republic, and the Ukrainian State. Following Germany's Armistice in World War I in November 1918, the states were abolished.

Finland was the first republic that declared its independence from Russia in December 1917 and established itself in the ensuing Finnish Civil War between pro-independence White Guards and pro-Russian Bolshevik Red Guards from January–May 1918. The Second Polish Republic, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia formed their own armies immediately after the abolition of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty and the start of the Soviet westward offensive and subsequent Polish-Soviet War in November 1918.

In the European part of Russia the war was fought across three main fronts: the eastern, the southern and the northwestern. It can also be roughly split into the following periods.

The first period lasted from the Revolution until the Armistice, or roughly March 1917 to November 1918. Already on the date of the Revolution, Cossack General Alexey Kaledin refused to recognize it and assumed full governmental authority in the Don region, where the Volunteer Army began amassing support. The signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk also resulted in direct Allied intervention in Russia and the arming of military forces opposed to the Bolshevik government. There were also many German commanders who offered support against the Bolsheviks, fearing a confrontation with them was impending as well.

During the first period, the Bolsheviks took control of Central Asia out of the hands of the Provisional Government and White Army, setting up a base for the Communist Party in the Steppe and Turkestan, where nearly two million Russian settlers were located.

Most of the fighting in the first period was sporadic, involved only small groups and had a fluid and rapidly shifting strategic situation. Among the antagonists were the Czechoslovak Legion, the Poles of the 4th and 5th Rifle Divisions and the pro-Bolshevik Red Latvian riflemen.

The second period of the war lasted from January to November 1919. At first the White armies' advances from the south (under Denikin), the east (under Kolchak) and the northwest (under Yudenich) were successful, forcing the Red Army and its allies back on all three fronts. In July 1919 the Red Army suffered another reverse after a mass defection of units in the Crimea to the anarchist Insurgent Army under Nestor Makhno, enabling anarchist forces to consolidate power in Ukraine. Leon Trotsky soon reformed the Red Army, concluding the first of two military alliances with the anarchists. In June the Red Army first checked Kolchak's advance. After a series of engagements, assisted by an Insurgent Army offensive against White supply lines, the Red Army defeated Denikin's and Yudenich's armies in October and November.

The third period of the war was the extended siege of the last White forces in the Crimea in 1920. General Wrangel had gathered the remnants of Denikin's armies, occupying much of the Crimea. An attempted invasion of southern Ukraine was rebuffed by the Insurgent Army under Makhno's command. Pursued into Crimea by Makhno's troops, Wrangel went over to the defensive in the Crimea. After an abortive move north against the Red Army, Wrangel's troops were forced south by Red Army and Insurgent Army forces; Wrangel and the remains of his army were evacuated to Constantinople in November 1920.

In the October Revolution, the Bolshevik Party directed the Red Guard (armed groups of workers and Imperial army deserters) to seize control of Petrograd and immediately began the armed takeover of cities and villages throughout the former Russian Empire. In January 1918 the Bolsheviks dissolved the Russian Constituent Assembly and proclaimed the Soviets (workers' councils) as the new government of Russia.

The first attempt to regain power from the Bolsheviks was made by the Kerensky-Krasnov uprising in October 1917. It was supported by the Junker Mutiny in Petrograd but was quickly put down by the Red Guard, notably including the Latvian Rifle Division.

The initial groups that fought against the Communists were local Cossack armies that had declared their loyalty to the Provisional Government. Kaledin of the Don Cossacks and General Grigory Semenov of the Siberian Cossacks were prominent among them. The leading Tsarist officers of the Imperial Russian Army also started to resist. In November, General Mikhail Alekseev, the Tsar's Chief of Staff during the First World War, began to organize the Volunteer Army in Novocherkassk. Volunteers of the small army were mostly officers of the old Russian army, military cadets and students. In December 1917, Alekseev was joined by General Lavr Kornilov, Denikin and other Tsarist officers who had escaped from the jail, where they had been imprisoned following the abortive Kornilov affair just before the Revolution. On 9 December, the Military Revolutionary Committee in Rostov rebelled, with the Bolsheviks controlling the city for five days until the Alekseev Organization supported Kaledin in recapturing the city. According to Peter Kenez, "The operation, begun on December 9, can be regarded as the beginning of the Civil War."

Having stated in the November 1917 "Declaration of Rights of Nations of Russia" that any nation under imperial Russian rule should be immediately given the power of self-determination, the Bolsheviks had begun to usurp the power of the Provisional Government in the territories of Central Asia soon after the establishment of the Turkestan Committee in Tashkent. In April 1917 the Provisional Government set up the committee, which was mostly made up of former Tsarist officials. The Bolsheviks attempted to take control of the Committee in Tashkent on 12 September 1917 but it was unsuccessful, and many leaders were arrested. However, because the Committee lacked representation of the native population and poor Russian settlers, they had to release the Bolshevik prisoners almost immediately because of a public outcry, and a successful takeover of that government body took place two months later in November. The Leagues of Mohammedam Working People (which Russian settlers and natives who had been sent to work behind the lines for the Tsarist government in 1916 formed in March 1917) had led numerous strikes in the industrial centers throughout September 1917. However, after the Bolshevik destruction of the Provisional Government in Tashkent, Muslim elites formed an autonomous government in Turkestan, commonly called the "Kokand autonomy" (or simply Kokand). The White Russians supported that government body, which lasted several months because of Bolshevik troop isolation from Moscow. In January 1918 the Soviet forces, under Lt. Col. Muravyov, invaded Ukraine and invested Kiev, where the Central Council of Ukraine held power. With the help of the Kiev Arsenal Uprising, the Bolsheviks captured the city on 26 January.

The Bolsheviks decided to immediately make peace with the Central Powers, as they had promised the Russian people before the Revolution. Vladimir Lenin's political enemies attributed that decision to his sponsorship by the Foreign Office of Wilhelm II, German Emperor, offered to Lenin in hope that, with a revolution, Russia would withdraw from World War I. That suspicion was bolstered by the German Foreign Ministry's sponsorship of Lenin's return to Petrograd. However, after the military fiasco of the summer offensive (June 1917) by the Russian Provisional Government had devastated the structure of the Russian Army, it became crucial that Lenin realize the promised peace. Even before the failed summer offensive the Russian population was very skeptical about the continuation of the war. Western socialists had promptly arrived from France and from the UK to convince the Russians to continue the fight, but could not change the new pacifist mood of Russia.

On 16 December 1917 an armistice was signed between Russia and the Central Powers in Brest-Litovsk and peace talks began. As a condition for peace, the proposed treaty by the Central Powers conceded huge portions of the former Russian Empire to the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire, greatly upsetting nationalists and conservatives. Leon Trotsky, representing the Bolsheviks, refused at first to sign the treaty while continuing to observe a unilateral cease-fire, following the policy of "No war, no peace".

Therefore, on 18 February 1918, the Germans began Operation Faustschlag on the Eastern Front, encountering virtually no resistance in a campaign that lasted 11 days. Signing a formal peace treaty was the only option in the eyes of the Bolsheviks because the Russian Army was demobilized, and the newly formed Red Guard could not stop the advance. The Soviets acceded to a peace treaty, and the formal agreement, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, was ratified on 3 March. The Soviets viewed the treaty as merely a necessary and expedient means to end the war.

In Ukraine, the German-Austrian Operation Faustschlag had by April 1918 removed the Bolsheviks from Ukraine. The German and Austro-Hungarian victories in Ukraine were caused by the apathy of the locals and the inferior fighting skills of Bolsheviks troops to their Austro-Hungarian and German counterparts.

Under Soviet pressure, the Volunteer Army embarked on the epic Ice March from Yekaterinodar to Kuban on 22 February 1918, where they joined with the Kuban Cossacks to mount an abortive assault on Yekaterinodar. The Soviets recaptured Rostov on the next day. Kornilov was killed in the fighting on 13 April, and Denikin took over command. Fighting off its pursuers without respite, the army succeeded in breaking its way through back towards the Don by May, where the Cossack uprising against the Bolsheviks had started.

The Baku Soviet Commune was established on 13 April. Germany landed its Caucasus Expedition troops in Poti on 8 June. The Ottoman Army of Islam (in coalition with Azerbaijan) drove them out of Baku on 26 July 1918. Subsequently, the Dashanaks, Right SRs and Mensheviks started negotiations with Gen. Dunsterville, the commander of the British troops in Persia. The Bolsheviks and their Left SR allies were opposed to it, but on 25 July the majority of the Soviets voted to call in the British and the Bolsheviks resigned. The Baku Soviet Commune ended its existence and was replaced by the Central Caspian Dictatorship.

In June 1918 the Volunteer Army, numbering some 9,000 men, started its Second Kuban campaign, capturing Yekaterinodar on 16 August, followed by Armavir and Stavropol. By early 1919, they controlled the Northern Caucasus.

On 8 October, Alekseev died. On 8 January 1919, Denikin became the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces of South Russia, uniting the Volunteer Army with Pyotr Krasnov's Don Army. Pyotr Wrangel became Denikin's Chief of Staff.

In December, three-fourths of the army was in the Northern Caucasus. That included three thousand of Vladimir Liakhov's soldiers around Vladikavkaz, thirteen thousand soldiers under Wrangel and Kazanovich in the center of the front, Stankevich's almost three thousand men with the Don Cossacks, while Vladimir May-Mayevsky's three thousand were sent to the Donets basin, and de Bode commanded two thousand in Crimea.

The revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion broke out in May 1918, and proceeded to occupy the Trans-Siberian Railway from Ufa to Vladivostok. Uprisings overthrew other Bolshevik towns. On 7 July, the western portion of the legion declared itself to be a new eastern front, anticipating allied intervention. According to William Henry Chamberlin, "Two governments emerged as a result of the first successes of the Czechs: the West Siberian Commissariat and the Government of the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly in Samara." On 17 July, shortly before the fall of Yekaterinburg, the former tsar and his family were murdered.

The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries supported peasants fighting against Soviet control of food supplies. In May 1918, with the support of the Czechoslovak Legion, they took Samara and Saratov, establishing the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly—known as the "Komuch". By July the authority of the Komuch extended over much of the area controlled by the Czechoslovak Legion. The Komuch pursued an ambivalent social policy, combining democratic and socialist measures, such as the institution of an eight-hour working day, with "restorative" actions, such as returning both factories and land to their former owners. After the fall of Kazan, Vladimir Lenin called for the dispatch of Petrograd workers to the Kazan Front: "We must send down the maximum number of Petrograd workers: (1) a few dozen 'leaders' like Kayurov; (2) a few thousand militants 'from the ranks'".

After a series of reverses at the front, the Bolsheviks' War Commissar, Trotsky, instituted increasingly harsh measures in order to prevent unauthorised withdrawals, desertions, and mutinies in the Red Army. In the field, the Cheka Special Investigations Forces (termed the Special Punitive Department of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combat of Counter-Revolution and Sabotage or Special Punitive Brigades) followed the Red Army, conducting field tribunals and summary executions of soldiers and officers who deserted, retreated from their positions, or failed to display sufficient offensive zeal. The Cheka Special Investigations Forces were also charged with the detection of sabotage and counter-revolutionary activity by Red Army soldiers and commanders. Trotsky extended the use of the death penalty to the occasional political commissar whose detachment retreated or broke in the face of the enemy. In August, frustrated at continued reports of Red Army troops breaking under fire, Trotsky authorised the formation of barrier troops – stationed behind unreliable Red Army units and given orders to shoot anyone withdrawing from the battle line without authorisation.

In September 1918, the Komuch, the Siberian Provisional Government, and other anti-Bolshevik Russians agreed during the State Meeting in Ufa to form a new Provisional All-Russian Government in Omsk, headed by a Directory of five: two Socialist-Revolutionaries. Nikolai Avksentiev and Vladimir Zenzinov, the Kadet lawyer V. A. Vinogradov, Siberian Premier Vologodskii, and General Vasily Boldyrev.

By the fall of 1918, anti-Bolshevik White forces in the east included the People's Army (Komuch), the Siberian Army (of the Siberian Provisional Government) and insurgent Cossack units of Orenburg, the Urals, Siberia, Semirechye, Baikal, and Amur and Ussuri Cossacks, nominally under the orders of Gen. V.G. Boldyrev, Commander-in-Chief, appointed by the Ufa Directorate.

On the Volga, Col. Kappel's White detachment captured Kazan on 7 August, but Red Forces recaptured the city on 8 September 1918 following a counteroffensive. On the 11th Simbirsk fell, and on 8 October Samara. The Whites fell back eastwards to Ufa and Orenburg.

In Omsk, the Russian Provisional Government quickly came under the influence and later the dominance of its new War Minister, the rear-admiral Kolchak. On 18 November, a coup d'état established Kolchak as supreme leader. Two members of the Directory were arrested, and subsequently deported, while Kolchak was proclaimed "Supreme Ruler", and "Commander-in-Chief of all Land and Naval Forces of Russia." By mid-December 1918, the White armies had to leave Ufa, but they balanced that failure with a successful drive towards Perm, which they took on 24 December.

In the Red Army, the concept of barrier troops first arose in August 1918 with the formation of the заградительные отряды (zagraditelnye otriady), translated as "blocking troops" or "anti-retreat detachments" (Russian: заградотряды, заградительные отряды, отряды заграждения). The barrier troops comprised personnel drawn from the Cheka punitive detachments or from regular Red Army infantry regiments.

The first use of the barrier troops by the Red Army occurred in the late summer and fall of 1918 in the Eastern front during the Russian Civil War, when Leon Trotsky authorized Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the commander of the 1st Army, to station blocking detachments behind unreliable Red Army infantry regiments in the 1st Red Army, with orders to shoot if front-line troops either deserted or retreated without permission.

In December 1918, Trotsky ordered that detachments of additional barrier troops be raised for attachment to each infantry formation in the Red Army. On December 18 he cabled:

How do things stand with the blocking units? As far as I am aware they have not been included in our establishment and it appears they have no personnel. It is absolutely essential that we have at least an embryonic network of blocking units and that we work out a procedure for bringing them up to strength and deploying them.

In 1919, 616 "hardcore" deserters of the total 837,000 draft dodgers and deserters were executed following Trotsky's draconian measures. According to Figes, "a majority of deserters (most registered as "weak-willed") were handed back to the military authorities, and formed into units for transfer to one of the rear armies or directly to the front". Even those registered as "malicious" deserters were returned to the ranks when the demand for reinforcements became desperate". Forges also noted that the Red Army instituted amnesty weeks to prohibit punitive measures against desertion which encouraged the voluntary return of 98,000-132,000 deserters to the army.

The barrier troops were also used to enforce Bolshevik control over food supplies in areas controlled by the Red Army as part of Lenin's war communism policies, a role which soon earned them the hatred of the Russian civilian population. These policies in part led to the Russian famine of 1921–1922, which killed about five million people. However, the famine was preceded by bad harvests, harsh winter, drought especially in the Volga Valley which was exacerbated by a range of factors including the war, the presence of the White Army and the methods of war communism. The outbreaks of diseases such as cholera and typhus were also contributing factors to the famine casualties.

On 6 July 1918, two Left Socialist-Revolutionaries and Cheka employees, Yakov Blumkin and Nikolai Andreyev, assassinated the German ambassador, Count Mirbach. In Moscow a Left SR uprising was put down by the Bolsheviks, mass arrests of Socialist-Revolutionaries followed, and executions became more frequent. Chamberlin noted, "The time of relative leniency toward former fellow-revolutionists was over. The Left Socialist Revolutionaries, of course, were no longer tolerated as members of the Soviets; from this time the Soviet regime became a pure and undiluted dictatorship of the Communist Party." Similarly, Boris Savinkov's surprise attacks were suppressed, with many of the conspirators being executed, as "Mass Red Terror" became a reality.

In February 1918, the Red Army overthrew the White Russian-supported Kokand Autonomy of Turkestan. Although that move seemed to solidify Bolshevik power in Central Asia, more troubles soon arose for the Red Army as the Allied Forces began to intervene. British support of the White Army provided the greatest threat to the Red Army in Central Asia during 1918. Britain sent three prominent military leaders to the area. One was Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Marshman Baile, who recorded a mission to Tashkent, from where the Bolsheviks forced him to flee. Another was General Wilfrid Malleson, leading the Malleson Mission, who assisted the Mensheviks in Ashkhabad (now the capital of Turkmenistan) with a small Anglo-Indian force. However, he failed to gain control of Tashkent, Bukhara and Khiva. The third was Major General Dunsterville, who was driven out by the Bolsheviks of Central Asia only a month after his arrival in August 1918. Despite setbacks as a result of British invasions during 1918, the Bolsheviks continued to make progress in bringing the Central Asian population under their influence. The first regional congress of the Russian Communist Party convened in the city of Tashkent in June 1918 in order to build support for a local Bolshevik Party.