|

|

|

|

|

The term "Bible" can refer to the Hebrew Bible or the Christian Bible, which contains both the Old and New Testaments.

The English word Bible is derived from Koinē Greek: τὰ βιβλία, romanized: ta biblia, meaning "the books" (singular βιβλίον, biblion). The word βιβλίον itself had the literal meaning of "scroll" and came to be used as the ordinary word for "book". It is the diminutive of βύβλος byblos, "Egyptian papyrus", possibly so called from the name of the Phoenician seaport Byblos (also known as Gebal) from whence Egyptian papyrus was exported to Greece.

The Greek ta biblia ("the books") was "an expression Hellenistic Jews used to describe their sacred books". The biblical scholar F. F. Bruce notes that John Chrysostom appears to be the first writer (in his Homilies on Matthew, delivered between 386 and 388 CE) to use the Greek phrase ta biblia ("the books") to describe both the Old and New Testaments together.

Latin biblia sacra "holy books" translates Greek τὰ βιβλία τὰ ἅγια (tà biblía tà hágia, "the holy books"). Medieval Latin biblia is short for biblia sacra "holy book". It gradually came to be regarded as a feminine singular noun (biblia, gen. bibliae) in medieval Latin, and so the word was loaned as singular into the vernaculars of Western Europe.

The Bible is not a single book; it is a collection of books whose complex development is not completely understood. The oldest books began as songs and stories orally transmitted from generation to generation. Scholars of the twenty-first century are only in the beginning stages of exploring "the interface between writing, performance, memorization, and the aural dimension" of the texts. Current indications are that writing and orality were not separate as much as ancient writing was learned in communal oral performance. The Bible was written and compiled by many people, who many scholars say are mostly unknown, from a variety of disparate cultures and backgrounds.

British biblical scholar John K. Riches wrote:

[T]he biblical texts were produced over a period in which the living conditions of the writers – political, cultural, economic, and ecological – varied enormously. There are texts which reflect a nomadic existence, texts from people with an established monarchy and Temple cult, texts from exile, texts born out of fierce oppression by foreign rulers, courtly texts, texts from wandering charismatic preachers, texts from those who give themselves the airs of sophisticated Hellenistic writers. It is a time-span which encompasses the compositions of Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, Sophocles, Caesar, Cicero, and Catullus. It is a period which sees the rise and fall of the Assyrian empire (twelfth to seventh century) and of the Persian empire (sixth to fourth century), Alexander's campaigns (336–326), the rise of Rome and its domination of the Mediterranean (fourth century to the founding of the Principate, 27 BCE), the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple (70 CE), and the extension of Roman rule to parts of Scotland (84 CE).

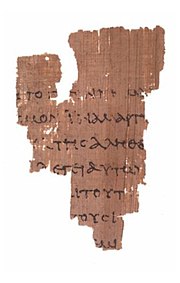

The books of the Bible were initially written and copied by hand on papyrus scrolls. No originals have survived. The age of the original composition of the texts is, therefore, difficult to determine and heavily debated. Using a combined linguistic and historiographical approach, Hendel and Joosten date the oldest parts of the Hebrew Bible (the Song of Deborah in Judges 5 and the Samson story of Judges 16 and 1 Samuel) to having been composed in the premonarchial early Iron Age (c. 1200 BCE). The Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered in the caves of Qumran in 1947, are copies that can be dated to between 250 BCE and 100 CE. They are the oldest existing copies of the books of the Hebrew Bible of any length that are not fragments.

The earliest manuscripts were probably written in paleo-Hebrew, a kind of cuneiform pictograph similar to other pictographs of the same period. The exile to Babylon most likely prompted the shift to square script (Aramaic) in the fifth to third centuries BCE. From the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Hebrew Bible was written with spaces between words to aid reading. By the eighth century CE, the Masoretes added vowel signs. Levites or scribes maintained the texts, and some texts were always treated as more authoritative than others. Scribes preserved and changed the texts by changing the script, updating archaic forms, and making corrections. These Hebrew texts were copied with great care.

Considered to be scriptures (sacred, authoritative religious texts), the books were compiled by different religious communities into various biblical canons (official collections of scriptures). The earliest compilation, containing the first five books of the Bible and called the Torah (meaning "law", "instruction", or "teaching") or Pentateuch ("five books"), was accepted as Jewish canon by the fifth century BCE. A second collection of narrative histories and prophesies, called the Nevi'im ("prophets"), was canonized in the third century BCE. A third collection called the Ketuvim ("writings"), containing psalms, proverbs, and narrative histories, was canonized sometime between the second century BCE and the second century CE. These three collections were written mostly in Biblical Hebrew, with some parts in Aramaic, which together form the Hebrew Bible or "TaNaKh" (an abbreviation of "Torah", "Nevi'im", and "Ketuvim").

There are three major historical versions of the Hebrew Bible: the Septuagint, the Masoretic Text, and the Samaritan Pentateuch (which contains only the first five books). They are related but do not share the same paths of development. The Septuagint, or the LXX, is a translation of the Hebrew scriptures and some related texts into Koine Greek and is believed to have been carried out by approximately seventy or seventy-two scribes and elders who were Hellenic Jews, begun in Alexandria in the late third century BCE and completed by 132 BCE. Probably commissioned by Ptolemy II Philadelphus, King of Egypt, it addressed the need of the primarily Greek-speaking Jews of the Graeco-Roman diaspora. Existing complete copies of the Septuagint date from the third to the fifth centuries CE, with fragments dating back to the second century BCE. Revision of its text began as far back as the first century BCE. Fragments of the Septuagint were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls; portions of its text are also found on existing papyrus from Egypt dating to the second and first centuries BCE and to the first century CE.

The Masoretes began developing what would become the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible in Rabbinic Judaism near the end of the Talmudic period (c. 300–c. 500 CE), but the actual date is difficult to determine. In the sixth and seventh centuries, three Jewish communities contributed systems for writing the precise letter-text, with its vocalization and accentuation known as the mas'sora (from which we derive the term "masoretic"). These early Masoretic scholars were based primarily in the Galilean cities of Tiberias and Jerusalem and in Babylonia (modern Iraq). Those living in the Jewish community of Tiberias in ancient Galilee (c. 750–950) made scribal copies of the Hebrew Bible texts without a standard text, such as the Babylonian tradition had, to work from. The canonical pronunciation of the Hebrew Bible (called Tiberian Hebrew) that they developed, and many of the notes they made, therefore, differed from the Babylonian. These differences were resolved into a standard text called the Masoretic text in the ninth century. The oldest complete copy still in existence is the Leningrad Codex dating to c. 1000 CE.

The Samaritan Pentateuch is a version of the Torah maintained by the Samaritan community since antiquity, which European scholars rediscovered in the 17th century; its oldest existing copies date to c. 1100 CE. Samaritans include only the Pentateuch (Torah) in their biblical canon. They do not recognize divine authorship or inspiration in any other book in the Jewish Tanakh. A Samaritan Book of Joshua partly based upon the Tanakh's Book of Joshua exists, but Samaritans regard it as a non-canonical secular historical chronicle.

The first codex form of the Hebrew Bible was produced in the seventh century. The codex is the forerunner of the modern book. Popularized by early Christians, it was made by folding a single sheet of papyrus in half, forming "pages". Assembling multiples of these folded pages together created a "book" that was more easily accessible and more portable than scrolls. In 1488, the first complete printed press version of the Hebrew Bible was produced.

During the rise of Christianity in the first century CE, new scriptures were written in Koine Greek. Christians eventually called these new scriptures the "New Testament" and began referring to the Septuagint as the "Old Testament". The New Testament has been preserved in more manuscripts than any other ancient work. Most early Christian copyists were not trained scribes. Many copies of the gospels and Paul's letters were made by individual Christians over a relatively short period of time, very soon after the originals were written. There is evidence in the Synoptic Gospels, in the writings of the early church fathers, from Marcion, and in the Didache that Christian documents were in circulation before the end of the first century. Paul's letters were circulated during his lifetime, and his death is thought to have occurred before 68 during Nero's reign. Early Christians transported these writings around the Empire, translating them into Old Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopic, and Latin, and other languages.

Bart Ehrman explains how these multiple texts later became grouped by scholars into categories:

During the early centuries of the church, Christian texts were copied in whatever location they were written or taken to. Since texts were copied locally, it is no surprise that different localities developed different kinds of textual tradition. That is to say, the manuscripts in Rome had many of the same errors, because they were for the most part "in-house" documents, copied from one another; they were not influenced much by manuscripts being copied in Palestine; and those in Palestine took on their own characteristics, which were not the same as those found in a place like Alexandria, Egypt. Moreover, in the early centuries of the church, some locales had better scribes than others. Modern scholars have come to recognize that the scribes in Alexandria – which was a major intellectual center in the ancient world – were particularly scrupulous, even in these early centuries, and that there, in Alexandria, a very pure form of the text of the early Christian writings was preserved, decade after decade, by dedicated and relatively skilled Christian scribes.

These differing histories produced what modern scholars refer to as recognizable "text types". The four most commonly recognized are Alexandrian, Western, Caesarean, and Byzantine.

The list of books included in the Catholic Bible was established as canon by the Council of Rome in 382, followed by those of Hippo in 393 and Carthage in 397. Between 385 and 405 CE, the early Christian church translated its canon into Vulgar Latin (the common Latin spoken by ordinary people), a translation known as the Vulgate. Since then, Catholic Christians have held ecumenical councils to standardize their biblical canon. The Council of Trent (1545–63), held by the Catholic Church in response to the Protestant Reformation, authorized the Vulgate as its official Latin translation of the Bible. A number of biblical canons have since evolved. Christian biblical canons range from the 73 books of the Catholic Church canon and the 66-book canon of most Protestant denominations to the 81 books of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church canon, among others. Judaism has long accepted a single authoritative text, whereas Christianity has never had an official version, instead having many different manuscript traditions.

All biblical texts were treated with reverence and care by those who copied them, yet there are transmission errors, called variants, in all biblical manuscripts. A variant is any deviation between two texts. Textual critic Daniel B. Wallace explains, "Each deviation counts as one variant, regardless of how many MSS [manuscripts] attest to it." Hebrew scholar Emanuel Tov says the term is not evaluative; it is a recognition that the paths of development of different texts have separated.

Medieval handwritten manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible were considered extremely precise: the most authoritative documents from which to copy other texts. Even so, David Carr asserts that Hebrew texts still contain some variants. The majority of all variants are accidental, such as spelling errors, but some changes were intentional. In the Hebrew text, "memory variants" are generally accidental differences evidenced by such things as the shift in word order found in 1 Chronicles 17:24 and 2 Samuel 10:9 and 13. Variants also include the substitution of lexical equivalents, semantic and grammar differences, and larger scale shifts in order, with some major revisions of the Masoretic texts that must have been intentional.

Intentional changes in New Testament texts were made to improve grammar, eliminate discrepancies, harmonize parallel passages, combine and simplify multiple variant readings into one, and for theological reasons. Bruce K. Waltke observes that one variant for every ten words was noted in the recent critical edition of the Hebrew Bible, the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, leaving 90% of the Hebrew text without variation. The fourth edition of the United Bible Society's Greek New Testament notes variants affecting about 500 out of 6900 words, or about 7% of the text.

The narratives, laws, wisdom sayings, parables, and unique genres of the Bible provide opportunity for discussion on most topics of concern to human beings: The role of women, sex, children, marriage, neighbours, friends, the nature of authority and the sharing of power, animals, trees and nature, money and economics, work, relationships, sorrow and despair and the nature of joy, among others. Philosopher and ethicist Jaco Gericke adds: "The meaning of good and evil, the nature of right and wrong, criteria for moral discernment, valid sources of morality, the origin and acquisition of moral beliefs, the ontological status of moral norms, moral authority, cultural pluralism, [as well as] axiological and aesthetic assumptions about the nature of value and beauty. These are all implicit in the texts."

However, discerning the themes of some biblical texts can be problematic. Much of the Bible is in narrative form and in general, biblical narrative refrains from any kind of direct instruction, and in some texts the author's intent is not easy to decipher. It is left to the reader to determine good and bad, right and wrong, and the path to understanding and practice is rarely straightforward. God is sometimes portrayed as having a role in the plot, but more often there is little about God's reaction to events, and no mention at all of approval or disapproval of what the characters have done or failed to do. The writer makes no comment, and the reader is left to infer what they will. Jewish philosophers Shalom Carmy and David Schatz explain that the Bible "often juxtaposes contradictory ideas, without explanation or apology".

The Hebrew Bible contains assumptions about the nature of knowledge, belief, truth, interpretation, understanding and cognitive processes. Ethicist Michael V. Fox writes that the primary axiom of the book of Proverbs is that "the exercise of the human mind is the necessary and sufficient condition of right and successful behavior in all reaches of life". The Bible teaches the nature of valid arguments, the nature and power of language, and its relation to reality. According to Mittleman, the Bible provides patterns of moral reasoning that focus on conduct and character.

In the biblical metaphysic, humans have free will, but it is a relative and restricted freedom. Beach says that Christian voluntarism points to the will as the core of the self, and that within human nature, "the core of who we are is defined by what we love". Natural law is in the Wisdom literature, the Prophets, Romans 1, Acts 17, and the book of Amos (Amos 1:3–2:5), where nations other than Israel are held accountable for their ethical decisions even though they do not know the Hebrew god. Political theorist Michael Walzer finds politics in the Hebrew Bible in covenant, law, and prophecy, which constitute an early form of almost democratic political ethics. Key elements in biblical criminal justice begin with the belief in God as the source of justice and the judge of all, including those administering justice on earth.

Carmy and Schatz say the Bible "depicts the character of God, presents an account of creation, posits a metaphysics of divine providence and divine intervention, suggests a basis for morality, discusses many features of human nature, and frequently poses the notorious conundrum of how God can allow evil."

| Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The authoritative Hebrew Bible is taken from the masoretic text (called the Leningrad Codex) which dates from 1008. The Hebrew Bible can therefore sometimes be referred to as the Masoretic Text.

The Hebrew Bible is also known by the name Tanakh (Hebrew: תנ"ך). This reflects the threefold division of the Hebrew scriptures, Torah ("Teaching"), Nevi'im ("Prophets") and Ketuvim ("Writings") by using the first letters of each word. It is not until the Babylonian Talmud (c. 550 BCE) that a listing of the contents of these three divisions of scripture are found.

The Tanakh was mainly written in Biblical Hebrew, with some small portions (Ezra 4:8–6:18 and 7:12–26, Jeremiah 10:11, Daniel 2:4–7:28) written in Biblical Aramaic, a language which had become the lingua franca for much of the Semitic world.

The Torah (תּוֹרָה) is also known as the "Five Books of Moses" or the Pentateuch, meaning "five scroll-cases". Traditionally these books were considered to have been dictated to Moses by God himself. Since the 17th century, scholars have viewed the original sources as being the product of multiple anonymous authors while also allowing the possibility that Moses first assembled the separate sources. There are a variety of hypotheses regarding when and how the Torah was composed, but there is a general consensus that it took its final form during the reign of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (probably 450–350 BCE), or perhaps in the early Hellenistic period (333–164 BCE).

The Hebrew names of the books are derived from the first words in the respective texts. The Torah consists of the following five books:

The first eleven chapters of Genesis provide accounts of the creation (or ordering) of the world and the history of God's early relationship with humanity. The remaining thirty-nine chapters of Genesis provide an account of God's covenant with the biblical patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (also called Israel) and Jacob's children, the "Children of Israel", especially Joseph. It tells of how God commanded Abraham to leave his family and home in the city of Ur, eventually to settle in the land of Canaan, and how the Children of Israel later moved to Egypt.

The remaining four books of the Torah tell the story of Moses, who lived hundreds of years after the patriarchs. He leads the Children of Israel from slavery in ancient Egypt to the renewal of their covenant with God at Mount Sinai and their wanderings in the desert until a new generation was ready to enter the land of Canaan. The Torah ends with the death of Moses.

The commandments in the Torah provide the basis for Jewish religious law. Tradition states that there are 613 commandments (taryag mitzvot).

Nevi'im (Hebrew: נְבִיאִים, romanized: Nəḇī'īm, "Prophets") is the second main division of the Tanakh, between the Torah and Ketuvim. It contains two sub-groups, the Former Prophets (Nevi'im Rishonim נביאים ראשונים, the narrative books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings) and the Latter Prophets (Nevi'im Aharonim נביאים אחרונים, the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel and the Twelve Minor Prophets).

The Nevi'im tell a story of the rise of the Hebrew monarchy and its division into two kingdoms, the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah, focusing on conflicts between the Israelites and other nations, and conflicts among Israelites, specifically, struggles between believers in "the LORD God" (Yahweh) and believers in foreign gods, and the criticism of unethical and unjust behaviour of Israelite elites and rulers; in which prophets played a crucial and leading role. It ends with the conquest of the Kingdom of Israel by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, followed by the conquest of the Kingdom of Judah by the neo-Babylonian Empire and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.

The Former Prophets are the books Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings. They contain narratives that begin immediately after the death of Moses with the divine appointment of Joshua as his successor, who then leads the people of Israel into the Promised Land, and end with the release from imprisonment of the last king of Judah. Treating Samuel and Kings as single books, they cover:

The Latter Prophets are Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the Twelve Minor Prophets, counted as a single book.

The books of Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah and Chronicles share a distinctive style that no other Hebrew literary text, biblical or extra-biblical, shares. They were not written in the normal style of Hebrew of the post-exilic period. The authors of these books must have chosen to write in their own distinctive style for unknown reasons.

The five relatively short books of Song of Songs, Book of Ruth, the Book of Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Book of Esther are collectively known as the Hamesh Megillot. These are the latest books collected and designated as authoritative in the Jewish canon even though they were not complete until the second century CE.

In Masoretic manuscripts (and some printed editions), Psalms, Proverbs and Job are presented in a special two-column form emphasizing their internal parallelism, which was found early in the study of Hebrew poetry. "Stichs" are the lines that make up a verse "the parts of which lie parallel as to form and content". Collectively, these three books are known as Sifrei Emet (an acronym of the titles in Hebrew, איוב, משלי, תהלים yields Emet אמ"ת, which is also the Hebrew for "truth"). Hebrew cantillation is the manner of chanting ritual readings as they are written and notated in the Masoretic Text of the Bible. Psalms, Job and Proverbs form a group with a "special system" of accenting used only in these three books.

Ketuvim (in Biblical Hebrew: כְּתוּבִים, romanized: Kəṯūḇīm "writings") is the third and final section of the Tanakh. The Ketuvim are believed to have been written under the inspiration of Ruach HaKodesh (the Holy Spirit) but with one level less authority than that of prophecy.

The following list presents the books of Ketuvim in the order they appear in most current printed editions.

The Jewish textual tradition never finalized the order of the books in Ketuvim. The Babylonian Talmud (Bava Batra 14b–15a) gives their order as Ruth, Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, Lamentations of Jeremiah, Daniel, Scroll of Esther, Ezra, Chronicles.

One of the large scale differences between the Babylonian and the Tiberian biblical traditions is the order of the books. Isaiah is placed after Ezekiel in the Babylonian, while Chronicles opens the Ketuvim in the Tiberian, and closes it in the Babylonian.

The Ketuvim is the last of the three portions of the Tanakh to have been accepted as canonical. While the Torah may have been considered canon by Israel as early as the fifth century BCE and the Former and Latter Prophets were canonized by the second century BCE, the Ketuvim was not a fixed canon until the second century CE.

Evidence suggests, however, that the people of Israel were adding what would become the Ketuvim to their holy literature shortly after the canonization of the prophets. As early as 132 BCE references suggest that the Ketuvim was starting to take shape, although it lacked a formal title. Against Apion, the writing of Josephus in 95 CE, treated the text of the Hebrew Bible as a closed canon to which "... no one has ventured either to add, or to remove, or to alter a syllable..." For an extended period after 95CE, the divine inspiration of Esther, the Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes was often under scrutiny.

The Septuagint ("the Translation of the Seventy", also called "the LXX"), is a Koine Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible begun in the late third century BCE.

As the work of translation progressed, the Septuagint expanded: the collection of prophetic writings had various hagiographical works incorporated into it. In addition, some newer books such as the Books of the Maccabees and the Wisdom of Sirach were added. These are among the "apocryphal" books, (books whose authenticity is doubted). The inclusion of these texts, and the claim of some mistranslations, contributed to the Septuagint being seen as a "careless" translation and its eventual rejection as a valid Jewish scriptural text.

The apocrypha are Jewish literature, mostly of the Second Temple period (c. 550 BCE – 70 CE); they originated in Israel, Syria, Egypt or Persia; were originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, and attempt to tell of biblical characters and themes. Their provenance is obscure. One older theory of where they came from asserted that an "Alexandrian" canon had been accepted among the Greek-speaking Jews living there, but that theory has since been abandoned. Indications are that they were not accepted when the rest of the Hebrew canon was. It is clear the Apocrypha were used in New Testament times, but "they are never quoted as Scripture." In modern Judaism, none of the apocryphal books are accepted as authentic and are therefore excluded from the canon. However, "the Ethiopian Jews, who are sometimes called Falashas, have an expanded canon, which includes some Apocryphal books".

The rabbis also wanted to distinguish their tradition from the newly emerging tradition of Christianity. Finally, the rabbis claimed a divine authority for the Hebrew language, in contrast to Aramaic or Greek – even though these languages were the lingua franca of Jews during this period (and Aramaic would eventually be given the status of a sacred language comparable to Hebrew).

The Book of Daniel is preserved in the 12-chapter Masoretic Text and in two longer Greek versions, the original Septuagint version, c. 100 BCE, and the later Theodotion version from c. second century CE. Both Greek texts contain three additions to Daniel: The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children; the story of Susannah and the Elders; and the story of Bel and the Dragon. Theodotion's translation was so widely copied in the Early Christian church that its version of the Book of Daniel virtually superseded the Septuagint's. The priest Jerome, in his preface to Daniel (407 CE), records the rejection of the Septuagint version of that book in Christian usage: "I ... wish to emphasize to the reader the fact that it was not according to the Septuagint version but according to the version of Theodotion himself that the churches publicly read Daniel." Jerome's preface also mentions that the Hexapla had notations in it, indicating several major differences in content between the Theodotion Daniel and the earlier versions in Greek and Hebrew.

Theodotion's Daniel is closer to the surviving Hebrew Masoretic Text version, the text which is the basis for most modern translations. Theodotion's Daniel is also the one embodied in the authorized edition of the Septuagint published by Sixtus V in 1587.

Textual critics are now debating how to reconcile the earlier view of the Septuagint as 'careless' with content from the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran, scrolls discovered at Wadi Murabba'at, Nahal Hever, and those discovered at Masada. These scrolls are 1000–1300 years older than the Leningrad text, dated to 1008 CE, which forms the basis of the Masoretic text. The scrolls have confirmed much of the Masoretic text, but they have also differed from it, and many of those differences agree with the Septuagint, the Samaritan Pentateuch or the Greek Old Testament instead.

Copies of some texts later declared apocryphal are also among the Qumran texts. Ancient manuscripts of the book of Sirach, the "Psalms of Joshua", Tobit, and the Epistle of Jeremiah are now known to have existed in a Hebrew version. The Septuagint version of some biblical books, such as the Book of Daniel and Book of Esther, are longer than those in the Jewish canon. In the Septuagint, Jeremiah is shorter than in the Masoretic text, but a shortened Hebrew Jeremiah has been found at Qumran in cave 4. The scrolls of Isaiah, Exodus, Jeremiah, Daniel and Samuel exhibit striking and important textual variants from the Masoretic text. The Septuagint is now seen as a careful translation of a different Hebrew form or recension (revised addition of the text) of certain books, but debate on how best to characterize these varied texts is ongoing.

Pseudepigrapha are works whose authorship is wrongly attributed. A written work can be pseudepigraphical and not be a forgery, as forgeries are intentionally deceptive. With pseudepigrapha, authorship has been mistransmitted for any one of a number of reasons. For example, the Gospel of Barnabas claims to be written by Barnabas the companion of the Apostle Paul, but both its manuscripts date from the Middle Ages.

Apocryphal and pseudepigraphic works are not the same. Apocrypha includes all the writings claiming to be sacred that are outside the canon because they are not accepted as authentically being what they claim to be. Pseudepigrapha is a literary category of all writings whether they are canonical or apocryphal. They may or may not be authentic in every sense except a misunderstood authorship.

The term "pseudepigrapha" is commonly used to describe numerous works of Jewish religious literature written from about 300 BCE to 300 CE. Not all of these works are actually pseudepigraphical. (It also refers to books of the New Testament canon whose authorship is questioned.) The Old Testament pseudepigraphal works include the following:

Notable pseudepigraphal works include the Books of Enoch such as 1 Enoch, 2 Enoch, which survives only in Old Slavonic, and 3 Enoch, surviving in Hebrew of the c. fifth century – c. sixth century CE. These are ancient Jewish religious works, traditionally ascribed to the prophet Enoch, the great-grandfather of the patriarch Noah. The fragment of Enoch found among the Qumran scrolls attest to it being an ancient work. The older sections (mainly in the Book of the Watchers) are estimated to date from about 300 BCE, and the latest part (Book of Parables) was probably composed at the end of the first century BCE.

Enoch is not part of the biblical canon used by most Jews, apart from Beta Israel. Most Christian denominations and traditions may accept the Books of Enoch as having some historical or theological interest or significance. Part of the Book of Enoch is quoted in the Epistle of Jude and the Book of Hebrews (parts of the New Testament), but Christian denominations generally regard the Books of Enoch as non-canonical. The exceptions to this view are the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

The Ethiopian Bible is not based on the Greek Bible, and the Ethiopian Church has a slightly different understanding of canon than other Christian traditions. In Ethiopia, canon does not have the same degree of fixedness, (yet neither is it completely open). Enoch has long been seen there as inspired scripture, but being scriptural and being canon are not always seen the same. The official Ethiopian canon has 81 books, but that number is reached in different ways with various lists of different books, and the book of Enoch is sometimes included and sometimes not. Current evidence confirms Enoch as canonical in both Ethiopia and in Eritrea.

A Christian Bible is a set of books divided into the Old and New Testament that a Christian denomination has, at some point in their past or present, regarded as divinely inspired scripture by the Holy Spirit. The Early Church primarily used the Septuagint, as it was written in Greek, the common tongue of the day, or they used the Targums among Aramaic speakers. Modern English translations of the Old Testament section of the Christian Bible are based on the Masoretic Text. The Pauline epistles and the gospels were soon added, along with other writings, as the New Testament.

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

|

The Old Testament has been important to the life of the Christian church from its earliest days. Bible scholar N. T. Wright says "Jesus himself was profoundly shaped by the scriptures." Wright adds that the earliest Christians searched those same Hebrew scriptures in their effort to understand the earthly life of Jesus. They regarded the "holy writings" of the Israelites as necessary and instructive for the Christian, as seen from Paul's words to Timothy (2 Timothy 3:15), as pointing to the Messiah, and as having reached a climactic fulfilment in Jesus generating the "new covenant" prophesied by Jeremiah.

The Protestant Old Testament of the 21st century has a 39-book canon. The number of books (although not the content) varies from the Jewish Tanakh only because of a different method of division. The term "Hebrew scriptures" is often used as being synonymous with the Protestant Old Testament, since the surviving scriptures in Hebrew include only those books.

However, the Roman Catholic Church recognizes 46 books as its Old Testament (45 if Jeremiah and Lamentations are counted as one), and the Eastern Orthodox Churches recognize six additional books. These additions are also included in the Syriac versions of the Bible called the Peshitta and the Ethiopian Bible.

Because the canon of Scripture is distinct for Jews, Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholics, and Western Protestants, the contents of each community's Apocrypha are unique, as is its usage of the term. For Jews, none of the apocryphal books are considered canonical. Catholics refer to this collection as "Deuterocanonical books" (second canon) and the Orthodox Church refers to them as "Anagignoskomena" (that which is read).

Books included in the Catholic, Orthodox, Greek, and Slavonic Bibles are: Tobit, Judith, the Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (or Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, the Letter of Jeremiah (also called the Baruch Chapter 6), 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, the Greek Additions to Esther and the Greek Additions to Daniel.

The Greek Orthodox Church, and the Slavonic churches (Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Ukraine, Russia, Serbia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Croatia) also add:

2 Esdras (4 Esdras), which is not included in the Septuagint, does not exist in Greek, though it does exist in Latin. There is also 4 Maccabees which is only accepted as canonical in the Georgian Church. It is in an appendix to the Greek Orthodox Bible, and it is therefore sometimes included in collections of the Apocrypha.

The Syriac Orthodox Church also includes:

The Ethiopian Old Testament Canon uses Enoch and Jubilees (that only survived in Ge'ez), 1–3 Meqabyan, Greek Ezra, 2 Esdras, and Psalm 151.

The Revised Common Lectionary of the Lutheran Church, Moravian Church, Reformed Churches, Anglican Church and Methodist Church uses the apocryphal books liturgically, with alternative Old Testament readings available. Therefore, editions of the Bible intended for use in the Lutheran Church and Anglican Church include the fourteen books of the Apocrypha, many of which are the deuterocanonical books accepted by the Catholic Church, plus 1 Esdras, 2 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh, which were in the Vulgate appendix.

The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches use most of the books of the Septuagint, while Protestant churches usually do not. After the Protestant Reformation, many Protestant Bibles began to follow the Jewish canon and exclude the additional texts, which came to be called apocryphal. The Apocrypha are included under a separate heading in the King James Version of the Bible, the basis for the Revised Standard Version.

| The Orthodox Old Testament |

Greek-based name |

Conventional English name |

| Law | ||

|---|---|---|

| Γένεσις | Génesis | Genesis |

| Ἔξοδος | Éxodos | Exodus |

| Λευϊτικόν | Leuitikón | Leviticus |

| Ἀριθμοί | Arithmoí | Numbers |

| Δευτερονόμιον | Deuteronómion | Deuteronomy |

| History | ||

| Ἰησοῦς Nαυῆ | Iêsous Nauê | Joshua |

| Κριταί | Kritaí | Judges |

| Ῥούθ | Roúth | Ruth |

| Βασιλειῶν Αʹ | I Basileiōn | I Samuel |

| Βασιλειῶν Βʹ | II Basileiōn | II Samuel |

| Βασιλειῶν Γʹ | III Basileiōn | I Kings |

| Βασιλειῶν Δʹ | IV Basileiōn | II Kings |

| Παραλειπομένων Αʹ | I Paraleipomenon | I Chronicles |

| Παραλειπομένων Βʹ | II Paraleipomenon | II Chronicles |

| Ἔσδρας Αʹ | I Esdras | 1 Esdras |

| Ἔσδρας Βʹ | II Esdras | Ezra–Nehemiah |

| Τωβίτ | Tōbit | Tobit or Tobias |

| Ἰουδίθ | Ioudith | Judith |

| Ἐσθήρ | Esther | Esther with additions |

| Μακκαβαίων Αʹ | I Makkabaion | 1 Maccabees |

| Μακκαβαίων Βʹ | II Makkabaion | 2 Maccabees |

| Μακκαβαίων Γʹ | III Makkabaion | 3 Maccabees |

| Wisdom | ||

| Ψαλμοί | Psalmoi | Psalms |

| Ψαλμός ΡΝΑʹ | Psalmos 151 | Psalm 151 |

| Προσευχὴ Μανάσση | Proseuchē Manassē | Prayer of Manasseh |

| Ἰώβ | Iōb | Job |

| Παροιμίαι | Paroimiai | Proverbs |

| Ἐκκλησιαστής | Ekklēsiastēs | Ecclesiastes |

| Ἆσμα Ἀσμάτων | Asma Asmatōn | Song of Solomon or Canticles |

| Σοφία Σαλoμῶντος | Sophia Salomōntos | Wisdom or Wisdom of Solomon |

| Σοφία Ἰησοῦ Σειράχ | Sophia Iēsou Seirach | Sirach or Ecclesiasticus or Wisdom of Sirach |

| Ψαλμοί Σαλoμῶντος | Psalmoi Salomōntos | Psalms of Solomon |

| Prophets | ||

| Δώδεκα | Dōdeka (The Twelve) | Minor Prophets |

| Ὡσηέ Αʹ | I Osëe | Hosea |

| Ἀμώς Βʹ | II Amōs | Amos |

| Μιχαίας Γʹ | III Michaias | Micah |

| Ἰωήλ Δʹ | IV Ioël | Joel |

| Ὀβδίου Εʹ | V Obdiou | Obadiah |

| Ἰωνᾶς Ϛ' | VI Ionas | Jonah |

| Ναούμ Ζʹ | VII Naoum | Nahum |

| Ἀμβακούμ Ηʹ | VIII Ambakoum | Habakkuk |

| Σοφονίας Θʹ | IX Sophonias | Zephaniah |

| Ἀγγαῖος Ιʹ | X Angaios | Haggai |

| Ζαχαρίας ΙΑʹ | XI Zacharias | Zachariah |

| Μαλαχίας ΙΒʹ | XII Malachias | Malachi |

| Ἠσαΐας | Ēsaias | Isaiah |

| Ἱερεμίας | Hieremias | Jeremiah |

| Βαρούχ | Barouch | Baruch |

| Θρῆνοι | Thrēnoi | Lamentations |

| Ἐπιστολή Ιερεμίου | Epistolē Ieremiou | Letter of Jeremiah |

| Ἰεζεκιήλ | Iezekiêl | Ezekiel |

| Δανιήλ | Daniêl | Daniel with additions |

| Appendix | ||

| Μακκαβαίων Δ' Παράρτημα | IV Makkabaiōn Parartēma | 4 Maccabees |